Community Profile: W̱SÁNEĆ’s ESKISELWET / Tracy Underwood

Among ESKISELWET / Tracy Underwood’s many accomplishments, she takes the most pride in being a mother of eight. “My drive is my children. They’re the reason why I do what I do,” says Tracy. In addition to being a devoted parent, Tracy is also an accomplished academic, currently in pursuit of her Ph.D.

Tracy’s career and academic history have always centred on helping her community; a veteran Family Service Social Worker, Tracy earned her First Nations Child and Youth Care Diploma in 1999. This was shortly followed up by her Bachelor of Arts degree in Child and Youth Care in 2001, and a Masters degree in the same field in 2010. Currently, Tracy works as an Instructor and Academic Coordinator for UVic’s Faculty of Human & Social Development and is a Ph.D. student in the School of Child & Youth Care. Her research is focused on ȽÁU,NOṈET SXEDQIṈEȽ (Healing House Post) messages of healing and hope, W̱SÁNEĆ resilience, the resurgence of SENĆOŦEN language and W̱SÁNEĆ culture.

Sharing the Lived Experience of the W̱SÁNEĆ People

Tracy’s successes have occurred in spite of many obstacles. In her academic journey, Tracy shares that it hasn’t been an easy road. Especially in her post-secondary studies, Tracy was often the only Indigenous woman in her class. The isolation of that experience is part of the reason Tracy started working on the JAE’ȽNONET (which means ‘To acknowledge and receive people’) presentation within and outside of UVic.

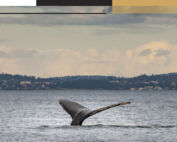

This project has taken many years of work. As part of Tracy’s Ph.D., JAE’ȽNONET is a narrative history of the Coast Salish people’s sequential existence and survival within the Songhees, Esquimalt, and W̱SÁNEĆ territories. On July 1st, 2021, Tracy was invited to give the presentation to a gathering of over two thousand people at the BC Legislature Lawn. The usual Canada Day celebrations were replaced by mourning for the Indigenous children whose lives were lost in the Residential School System.

“You could hear a pin drop,” remembers Tracy of that day. The audience listened in silence as Tracy shared Coast Salish population statistics on the Saanich Peninsula, which was estimated to be around 18,500 before settler contact to a mass genocide of less than 600, from the 1850’s to early 1900’s (about 50 years). Tracy also shares her own stories gathered from Knowledge Holders within the communities of the devastating intergenerational losses that continue to impact Coast Salish families today.

“People think I’m an exception and don’t experience the continued genocide (the Indian Act still imposes) because I have a master’s degree and I’m working on my Ph.D. So, I must be special. I must be immune—those things of the past don’t affect me because look what I did. But every day, every single day, all those things affect my life. I think it’s a good day when they don’t, but every day they do,” shares Tracy about her personal relationship to her work on JAE’ȽNONET.

“I think, mainly, that I do my presentation at UVic because it’s a response to the land acknowledgment. They do a land acknowledgment, but do they know what they’re actually saying when they do that? Well-meaning settlers have always caused our people harm, unknowingly and knowingly,” says Tracy. Giving the JAE’ȽNONET presentation is part of her work to shed light on the realities of the intergenerational loss experienced within W̱SÁNEĆ communities, helping settlers realize that the path to witness Rebuilding (reconciliation) and deeper understanding will require much more than a land acknowledgment, and begins with an admission of not fully knowing what W̱SÁNEĆ people go through in their everyday lives.

“I also do my little disclaimer that I don’t pretend to know everything. I just share from my life growing up here and what I learned. I acknowledge the information I got from the Saltwater People book I use, the Songhees and Esquimalt websites, speaking to elders and my friends and family,” says Tracy.

On Persistent Dehumanizing Trauma Response

Tracy is equally passionate about addressing systemic racism in social institutions. Ingrained discriminatory behaviors in places like schools, hospitals, and other social service agencies instill fear and cause what Tracy calls Persistent Dehumanizing Trauma Response (PDTR). PDTR is a term Tracy is advocating to be included in the medical lexicon when referring to the experience of Indigenous people at the hands of systemic racism. “It’s different from PTSD because it’s ongoing and part of daily life for us. The persistent part of PDTR explains the experience of ongoing dehumanizing of Indigenous people within all the systems (racism in medical, education, justice systems),” Tracy shares.

In a very personal example of PDTR, Tracy, like so many of her relatives and community members has had to manage a harrowing brush with the Ministry of Children and Family Development (MCFD), for circumstances that would have caused quite a different outcome for a non-Indigenous family.

Upon receiving communication from MCFD, “I was freaking out. I cried myself to sleep worried about what they wanted. I didn’t know what they wanted or what they were going to want. And if they come into my life, they’re going to entangle me in it and it’s going to be hard to get out. I went into instant PDTR,” remembers Tracy. She phoned MCFD the following day and met with an agent during her lunch hour.

The agent told her that the doctor who treated her son for a minor injury he sustained while playing called them in because Tracy’s son wouldn’t talk to him. Having worked as a Family Social Worker before, Tracy challenged this as a valid child protection concern. Nevertheless, the agent told her that MCFD would need to come into their family home as standard protocol.

After what was a long, dehumanizing and upsetting process, Tracy successfully closed out the case with MCFD. At first, Tracy wanted nothing more to do with the hospital that filed the report. But she was encouraged by a friend to return to tell them about the needless harm they had caused her and her family. Tracy was hesitant but finally decided that she needed to say something, “I do have to tell them to do better. I want this hospital accessible to my children and my grandchildren.”

Tracy wrote a victim impact statement and called for a meeting with the doctor who was responsible for bringing MCFD into the situation. The meeting was attended by the doctor in question accompanied by the Director of the Hospital and more senior staff. Tracy read her victim impact statement in the meeting and she had brought eagle feathers with her to give to the doctors who were in attendance. Each feather was attached to a paddle where one side was engraved the names of the four First Nations Saanich Communities— Tsartlip, Pauquachin, Tseycum, and Tsawout—and on the other side was simply “W̱SÁNEĆ.”

“I told him this means that we are the people who have risen,” remembers Tracy after reading her victim impact statement to the group. “When I gave him the eagle feather, I was still choked up crying. And I said, ‘When we come here, we’re only asking for help.’” Tracy remembers the doctor crying as he said to her, “I’m the one who caused harm, but I’m the one who gets a gift? What can I do?” In reply, Tracy said to him: “All I want you to do is follow the path you took—the oath to do no harm. And now you know.” The doctor told her that he would hang the eagle feather above his door to remind him every day to do better. The hospital changed their MCFD reporting process, and the doctor retracted their MCFD report stating that they filed the child protection report as a mis-step.

In Tracy’s current efforts, she is working to insist settlers do better. By presenting JAE’ȽNONET in as many areas as possible she’s drawing awareness to the horrible history of loss W̱SÁNEĆ people have experienced on the Saanich Peninsula. By working to have PTDR and its definition included in the medical lexicon, Tracy hopes it will help both Indigenous and settlers better understand the cumulative impacts of systemic racism on Indigenous people. Finally, by continuing the pursuit of her Ph.D., Tracy is creating a better world for her children and grandchildren.

Stay up to date on this story and others, sign up for our newsletter.