From the 1940’s to 1990’s, many W̱SÁNEĆ women knit to feed their families.

As part of WLC’s mission to promote respect for W̱SÁNEĆ culture, this is the first of a three-part series honouring the history of knitting and W̱SÁNEĆ knitters.

The history of W̱SÁNEĆ knitters

“The average person thinks of a Cowichan sweater as a three-tone, chunky, geometric pattern knit, but to me, it represents survival. I believe my grandmother raised my father and his siblings off her knitting. I am very proud to be a Coast Salish knitter, there’s pride in the resiliency of the history of it.” Joni Olsen

Tommy Paul, David Latess, and Edward Jim in traditional blankets

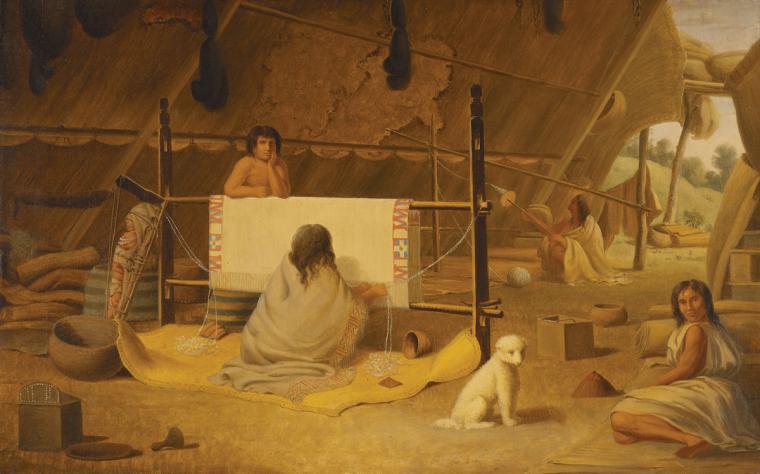

Coast Salish women have worked with wool for thousands of years. Before colonizers landed in the territory, W̱SÁNEĆ women were held in particularly high regard because they produced the most valuable currency, woven blankets. These blankets were originally made from goat wool combined with the wool from the Salish Woolly Dog, bred specifically for this purpose.

Shown above top: Images of Coast Salish knitters with the Salish Woolly Dog.

Shown above bottom: A photo of the Coast Salish Woolly Dog taken on Tsawout about 1935

When colonizers arrived in Coast Salish Territory, they introduced manufactured blankets which disrupted the blanket economy and shifted Coast Salish women’s role away from being primary currency producers.

It was also during this period that W̱SÁNEĆ food systems became destabilized. The laws of the colonial government restricted W̱SÁNEĆ to living on reserves and criminalized many aspects of W̱SÁNEĆ culture, including hunting and fishing. Because of these restrictions, it became far more difficult for W̱SÁNEĆ to live off the land in the traditional manner. Racism also made it difficult for Indigenous men to work and earn the money they needed to buy food. The combination of these factors created a serious risk to the survival of W̱SÁNEĆ people.

However, Coast Salish women were quick to adapt to the European influence and started working with the new materials, sheep’s wool and knitting needles, in order to earn money to feed their children. It didn’t take long before an entire industry emerged from their knitting.

In addition to clothing their families, a great demand for W̱SÁNEĆ knitting came from the settlers who were working outside in the wet and cold, fishing and farming.

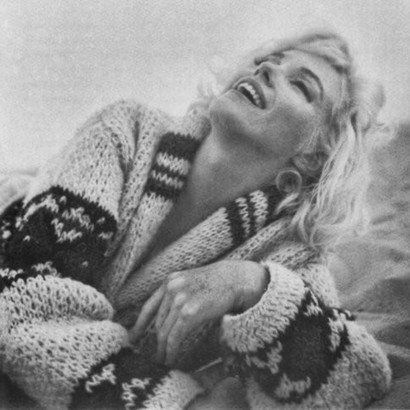

Shown above, the Cowichan sweater worn by settlers

The popularity of the sweaters soared and the Indian Sweater became a booming business. Although the Cowichan Sweater was a thriving industry, the women who knit them were greatly underpaid for their work. Some institutions who bought the sweaters would insist on paying the knitters in overpriced wool. If they were paid in cash, the amounts paid did not reflect the days of work that went into creating them. In the 1970’s the Mount Newton Indian Sweater business opened in W̱SÁNEĆ, this business provided an alternative, fair place for W̱SÁNEĆ knitters to buy wool and sell their goods.

Federal and provincial governments have often gifted Cowichan sweaters as a symbol of Canada to foreign elites and celebrities, such as Pope John Paul II, Prince Charles and Lady Diana, Harry Truman and Bing Crosby. Unfortunately, the popularity of the sweater eventually led to replications and mass production. Appropriated designs became rampant, seen on celebrities like Marilyn Monroe. Several disputes over appropriation were initiated and won by the Cowichan Tribe; the most notable of which was in 2010 when the Hudson’s Bay company sold mass produced replicates as official Olympic merchandise. What were first known as “Indian Sweaters,” and are now commonly known as Cowichan sweaters, have become a cultural icon.

Throughout history, the majority of the women who knit sweaters to feed their families have been largely left out of the conversation. Even the name “Cowichan Sweater” doesn’t tell the full story of the Coast Salish knitters. According to Sylvia Olsen, author of Working with Wool: A Coast Salish Legacy and the Cowichan Sweater, “A proportional number of knitters come from Sooke, Songhees, Saanich, Malahat, Chemainus, Kuper Island, Nanaimo, and mainland communities such as Musqueam, Squamish, and Burrard.”

In part one of the three part series Honouring the W̱SÁNEĆ knitters, we share the stories of just a few of the W̱SÁNEĆ women alive during this time, as told to the WLC by their families.

Madelyn Morris:

When we asked her daughter Ivy to tell us what she remembered about her mother’s knitting she replied “It was a way of life for my late mother.”

Shown above Madeline Morris, a prolific W̱SÁNEĆ knitter

Born in 1931, and the mother of 6, Madeline learned knitting from her own mother who knit using the traditional materials; the woolly dog and goat. Madeline, like many knitters of that era, started when she was just a child. “It’s in our teachings to pass on knowledge as young as possible,” Ivy explains.

In contrast to modern knitters of today who simply buy ready-made yarn and wool, Madeline and the other young women who knit would travel to the Gulf Islands to harvest sheep’s wool by hand.

Ivy recalls, “It was a lot of labour. After harvesting they’d wash the wool outside in a big barrel with boiling water, scrub it clean and make sure it was the white it was supposed to be. Then she’d hang it in the line or on the rocks. When the sun is shining it doesn’t take too long to dry. Then she’d collect it all and bring it back home.”

Once the wool was collected, every part of the wool would need to be pulled apart, Ivy remembers. “She used the word tease to describe the stretching of the wool.”

After that, the carding would be done, by hand, in 10 inches by 5-inch sections using carding paddles. Carding is the step before turning the wool into a thread which was done by spreading the teased and carded wool into neat piles, about an inch wide. Finally, the spinning process would begin. Madeline’s late father, Ivy’s grandfather Moodie Henry built Madeline a spinner that still works.

Madeline Morris’ spinner as made by her late father, which still works.

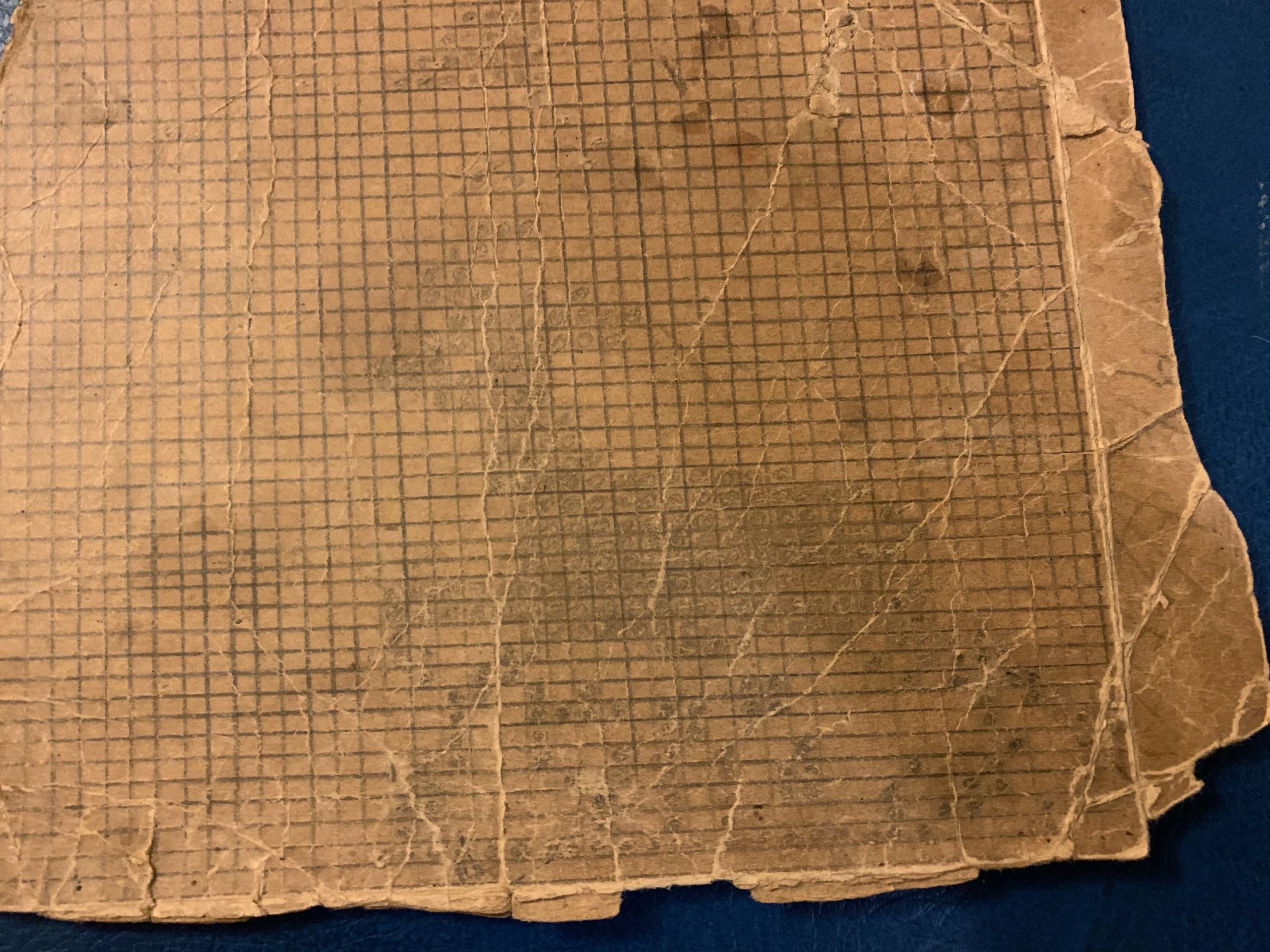

Ivy remembers her mother spinning the wool into all the different creations. Specifically, the design made by her father Moodie, called “dancing deer.” Ivy shares a faded copy of the hardcopy of the design and an example of the design in use today.

The dancing deer pattern, created by Moodie Henry and knitted by Madeline Morris

“She memorized the dancing deer. She didn’t need to look at the pattern. This put food on the table for our families,” Ivy remembers. “At that time period, there was a lot of racism. It was hard for people to get a job, coming out of traditional ways, adapting out of the traditional.”

Laura Olsen:

Born in 1915, Laura is remembered as knitting for the majority of her life. She started at around 10 years old and continued until she passed away at 93.

Like most W̱SÁNEĆ women, she learned from her mother and sisters while helping out as a kid. Laura was known for designing her own patterns as well as knitting them.

Laura’s middle son, Carl Olsen shares with us, “I remember her knitting sweaters, toques and socks for inside the boots, which were great, especially for if you were out digging clams. She would figure out her own way for figuring out how to make socks.”

The process of making the socks, sweaters and toques was arduous and started with gathering wool from local farmers. The wool would still be on the hide and would need to be removed using a razor blade. All Laura’s children would help to process the wool which would then be washed, dried out in the sun and teased to remove branches, brushed and washed again. Then it would be spun into yarn and ready for knitting.

What Laura did was far more than knitting, she was feeding her family. Carl remembers:

“What she did was knit so we could eat. There were 12 of us and there needed to be a way to supplement my dad’s income. He was a fisherman and logger but the wages weren’t that good. With his work, he paid the bills. With her work, she made the meals. All of her knitting was to put food on the table.”

Laura worked days and evenings to make sweaters which would then be sold for around $40, a paltry sum for two days of hard work. However, there were only two or three stores that would buy the sweaters. Then, the stores started to supply wool and insisted that payment was made in wool, which made it even harder to earn money to feed her family.

There was a baker from what is now called Sidney who would trade bread to knitters during his weekly visit through the reserve. This was another way of getting food on the table.

Carl remembers watching her knit: “She didn’t even look at the pattern book. The pattern would show up. She did many different patterns, the wave pattern was always nice looking. She did a nice eagle.”

Nora Tom

Nora Tom was born in 1931 and passed in 2011. Nora, like many women of her generation, knitted for virtually her entire life, up to 5 years before she passed.

Nora’s daughter Patricia told the WLC that Nora’s knitting supported her immediate and extended family with food and clothing. Nora would knit toques, vests, sweaters, scarves and socks.

Patricia shares, “Our family had 9 kids that survived, 12 kids originally. My dad’s mother also stayed with us. Then on weekends sometimes my dad would be gone. My mom was home, plus my auntie’s and uncle’s kids, in a little 3 bedroom house and preparing supper while she was knitting. She’d be taking care of 12-16 kids.”

This was in addition to what was a more than full-time knitting job. Prior to knitting, the wool would need at least a day of preparation; washing, drying, teasing, carding, spinning and rolling it so it wouldn’t get tangled.

Coast salish women preparing raw wool for knitting

Like her contemporaries, Nora learned how to prepare the wool and knit as a child. In turn, her daughters learned from and helped her.

Patrica said “Back then we had to help her tease the wool, take out all the burdocks and tiny branches that were stuck in the wool to clean it. She would give us hand carders and we would have to hand-card it. She was doing her part on a big carder. Sometimes she’d call us to do the plain parts. She’d do the collar and the arms, Sometimes she’d be doing two sweaters at a time. Us girls would help her”

When Nora was younger, she’d sometimes get together with other ladies who knit.

Shown above: Coast Salish Women knitting to feed their families

“Sometimes she’d be stressed because we needed food. So she would knit all day and all night to get one sweater done. That was her job. She kept us clean and fed,” Patrica remembers.

Once the sweaters were finished, Nora would take them to Sylvia Olsen, who would put a zipper on the sweater. Then Nora could sell it for $50-$65 per sweater. “They were getting ripped off,” Patricia shares.

Cecilia Smith

Cecilia’s daughter, Cynthia remembers her mother’s knitting with pride, “She was one of the top knitters. It was awesome to see how far she went.”

Cecilia started knitting at 8 years old and stopped in her 80’s, just a few years before she died. She knit sweaters, vests, toques, mittens, slippers and purses to support her family of 12. As was the norm, she’d buy the wool herself and prepare it from scratch and then have it carded before she started knitting.

Cynthia remembers, “I even got her into this cute business, I used to house clean and I worked with this older lady that made teddy bears. Mom knitted sweaters for the teddy bears and she made it into a teddy bear book.”

Cecilia was asked to teach but declined, Cynthia laughs, “She said no because she couldn’t knit slowly. She wouldn’t even have to look. She could watch tv, or talk to me without even looking, she would be so fast.”

Cecilia would knit until she got a bag full of clothing. Then she’d press them, get them zippered and travel on the bus to Victoria to go to a trading post store and sell her sweaters there. Cynthia shares, “Her knitting ended up all over the world. Late Princess Diana and her boys wore her sweaters.”

Shown above, a trading post store stocked with Cowichan Sweaters

“Once the knitting was sold, Cecilia would shop for her family and my sister, even though she’d moved away. There were 12 kids. Everyone in the family got something from her.”

“She didn’t even need to look at the designs anymore, they were in her brain. That’s what she told me.” Cynthia shares.

Honouring W̱SÁNEĆ knitters who have passed

These are the stories of just a few W̱SÁNEĆ knitters who have since passed. Their decades of strenuous labour ensured their families’ survival against incredible odds.

A few of the other knitters whose relatives we could not reach in time to publish this article were:

Roberta Jimmy

Tilly (Bill) Sam

Frankie Bill

Colin Jimmy

Beatrice Elliott

Stay tuned for the next article honouring W̱SÁNEĆ knitters. Don’t miss a thing! Sign up for our newsletter or join us on social media.

RECENT POSTS

How are we doing?

“What she did was knit so we could eat. There were 12 of us and there needed to be a way to supplement my dad’s income. He was a fisherman and logger but the wages weren’t that good. With his work, he paid the bills. With her work, she made the meals. All of her knitting was to put food on the table.” Carl Olsen, remembering his late mother