The Salish Sea Garden Project continues to restore traditional food sources & knowledge

Since 2015, W̱SÁNEĆ knowledge holders, in partnership with Parks Canada, have been working to restore sea gardens in the Salish Sea.

Shown above: sea garden restoration in Fulford Harbour over two nights in November.

This project has not only improved the ancient clam beds, but has also reclaimed traditional knowledge and restored W̱SÁNEĆ access and connection to the land.

Phase One: The Clam Garden Initiative

Initially called the Clam Garden initiative, the project’s first phase was a pilot project from 2014-2019 to experimentally restore two clam gardens by managing them as W̱SÁNEĆ people have for thousands of years.

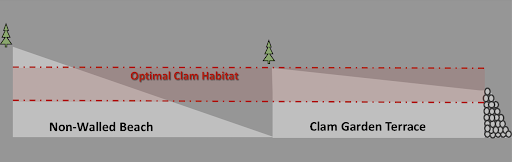

A clam garden is characterized by a rock wall at the low tide line that traps sediment and expands the habitat in which clams flourish. The rock wall also acts as a reef-like habitat, creating homes for kelps, fish, and other important foods that would otherwise not appear in these areas.

Shown above, a diagram of a sea garden

Many clam gardens in the area are over 3,000 years old. W̱SÁNEĆ people tend clam gardens through aeration, debris removal, and selective harvesting. These practices encourage growth of many valuable food species in the shallow coastal waters. Once established, clam gardens support up to 2x more clams than unmodified beaches.

In a video documenting The Clam Garden project, W̱SÁNEĆ Elder Jim Elliott shares:

“Clam harvesting has been important to our people for thousands of years. I believe it is one of the unique attractions to the coastline for Salish people. All year round you’d have a very valuable source of protein, right at your front door.”

The results of the clam garden initiative were positive from both a W̱SÁNEĆ and Western Perspective. Ally Stocks, the Project Manager of the Clam Garden Restoration Project for Parks Canada, noted that the clam gardens had more baby clams and showed increases in the density of native species than the average beach. From an Indigenous perspective, there were also improvements in the way the beaches looked and the number of squirting clams that could be seen. The health of the overall area was increased and the beaches were more likely to elicit the response, “This is a place I would cultivate.’”

The Clam Garden restoration project also provided scientists with data on traditional clam cultivating and harvesting practices while restoring traditional W̱SÁNEĆ knowledge related to clam gardens and their inhabitants: ȽÁU,₭EM/mussels, and ṮEX̱ṮEX̱/oysters, SQȽÁ ̧I ̧,/ittleneck clams, S’OX̱E/butter clams, ŚW̱ AAM/horse clam and ḴEXÁLS/digging clams.

In a report penned by Joni Olsen in late-2019, she detailed the methods by which hundreds of highly productive clam gardens were managed by W̱SÁNEĆ people throughout history. Included in the report were W̱SÁNEĆ Laws, W̱SÁNEĆ protocol for clam harvesting in a good way, SENĆOŦEN words relating to clam harvesting, and practical techniques for building and maintaining clam gardens.

The project was the first of its kind and drew interest internationally from both the scientific community and neighboring Indigenous nations in the US. Members of the Swinomish Nation from Washington State visited to learn and participate in the project, bringing W̱SÁNEĆ traditional knowledge back to their own communities for use in their clam gardens. W̱SÁNEĆ and Hul’q’umi’num Elders, harvesters, and youths were joined on the Saltspring and Russell Island Clam Garden sites by scholars from Royal Roads University, Simon Fraser University and the University of Saskatchewan.

Beyond knowledge reclamation and ecological restoration, the project resulted in additional positive outcomes for the participants and the community at large. Learning in an intergenerational way and being able to cultivate and access reinstated food systems were significant benefits to being involved in the project.

Phase two: The Sea Garden Initiative

Although the Sea Garden Initiative came to a virtual standstill at the beginning of the pandemic, Parks Canada staff have been working closely with the W̱SÁNEĆ traditional knowledge working group to get the project back underway and regain lost momentum. The W̱SÁNEĆ traditional knowledge working group consists of the following participants: Aaron Sam Sr, Tom Smith, Rob Sampson, John Elliott (J,SIṈTEN), Carl Olsen, James Jimmy, Gus Jimmy and the Pauquachin Marine Team. There has also been a lot of support and participation from Richard Underwood and Reanne Askham from the Tsawout First Nation Fisheries department.

Together, Parks Canada staff and the W̱SÁNEĆ traditional knowledge working group have designed the second phase (“From Healthy Clams to Sustainable Seas”) to build on lessons learned from the first phase of the Clam Garden Restoration Project and expand the scope to create healthy, sustainable ecosystems.

Reflecting on this, Ally Stocks stated: “What we’ve learned is that it’s not just about clams . . . there’s not a direct translation for clam garden. A better name is Sea Garden. We want to look at other key species that are missing

The widened scope of the project will include new active management techniques and innovative research, in addition to continued maintenance and monitoring at the four target restoration sites: 1. Fulford Harbour 2, Russel Island 3. Winter Cove on Saturna Island 4. Cabbage Island, just off Saturna Island. Further, these sites will be maintained in line with three new project pillars as identified by the Indigenous Knowledge Holders and key Indigenous stakeholders.

Pillar 1: Completing the sea garden system so that it can be self-sustaining with continued Indigenous stewardship.

In this pillar, Indigenous Knowledge Holders continue to be supported to maintain regular restoration of the rock walls and beach tending practices that support healthy ecosystems.

Unfortunately, COVID-19 has presented a major challenge. Where W̱SÁNEĆ people don’t have access to boats, ensuring safe transport has proven challenging. During this phase, the program has contracted boats from Tseycum community members and used Parks Canada boats to provide transport to the sea garden sites.

Ensuring regular W̱SÁNEĆ access to sea garden sites is critical in order to maintain the rock walls and tend the beach to keep it healthy. The practice of tilling or “fluffing” the sediment, according to Indigenous Knowledge Holders both releases toxins and increases the flow of nutrients to the clams and other species that would otherwise be compacted under dense sediment. Compacted beaches harbor less diversity than non-groomed beaches.

Related to the regular maintenance of sea gardens, Knowledge Holders have identified key species that are currently missing from the sea garden sites. Returning these species is an important milestone to achieve in order for the ecosystem to function as before when Indigenous management practices were consistent.

Shown above: Over two chilly nights in the November of 2021, the Sea Garden initiative participants, led by Indigenous Knowledge holders, restored sea garden walls and tilled the sediment at winter’s lowest tide, around midnight.

Pillar 2: Coast Salish Peoples are safely harvesting and eating sea garden species.

Currently, all requests to test shellfish must be channeled through the Department of Fisheries and Oceans Canada, the Canadian Food Inspection Agency, and Environment and Climate Change Canada, which together form the Canadian Shellfish Sanitation Program. In its current form, this process is challenging to navigate for W̱SÁNEĆ harvesters.

As it stands, there are many closures to shellfish harvest due to different contaminants or lack of testing, which is a major obstacle the project is working to eliminate. One of the paths to do so would be to ensure W̱SÁNEĆ monitors are at sea garden sites and have the training and skills necessary to conduct testing locally to determine contaminant levels.

“We are working to support innovative work and a paradigm shift around how contaminants are monitored and how people can determine whether it’s safe to eat traditional food from the sea gardens,” shares Bryant Deroy, the Sea Garden Initiative Science Officer at Parks Canada.

Shown above: Clam species labeled for scientific monitoring

Pillar 3: Cowichan and W̱SÁNEĆ Nations are leading and managing sea gardens with sustainable funding

The third pillar focuses on ensuring adequate resources for Cowichan and W̱SÁNEĆ Nations to reclaim the leadership and management of the sea gardens. These resources consist of both funding resources as well as human resources.

For the Sea Garden Initiative to be sustainable, the practices and knowledge must be passed on to future generations.

Shown above, from left to right: Bear Horne, Beangka Elliott, Aaron Sam Sr., Richard Underwood stay warm during the two-day sea garden maintenance that took place on Fulford Harbour in late November

The third pillar focuses on creating further Indigenous-directed opportunities for knowledge transfer for children, youth, and adults in all aspects of sea garden management.

Another initiative under the project is to update the signage and visibility around these sites. Current signage and artwork aren’t reflective of information about Indigenous practices at these Sea Garden sites.

After a successful late-November Sea Garden trip to the Fulford site, more site visits are planned in January.

To stay up to date on this story, please sign up for our newsletter.