This February 11th, 2022 marks the 170th anniversary of the signing of the Douglas Treaties.

The Douglas Treaties are a complex topic that affects the lives of W̱SÁNEĆ people every day. While W̱SÁNEĆ people know what really happened, we have to consider both the written and oral versions of the Douglas Treaties.

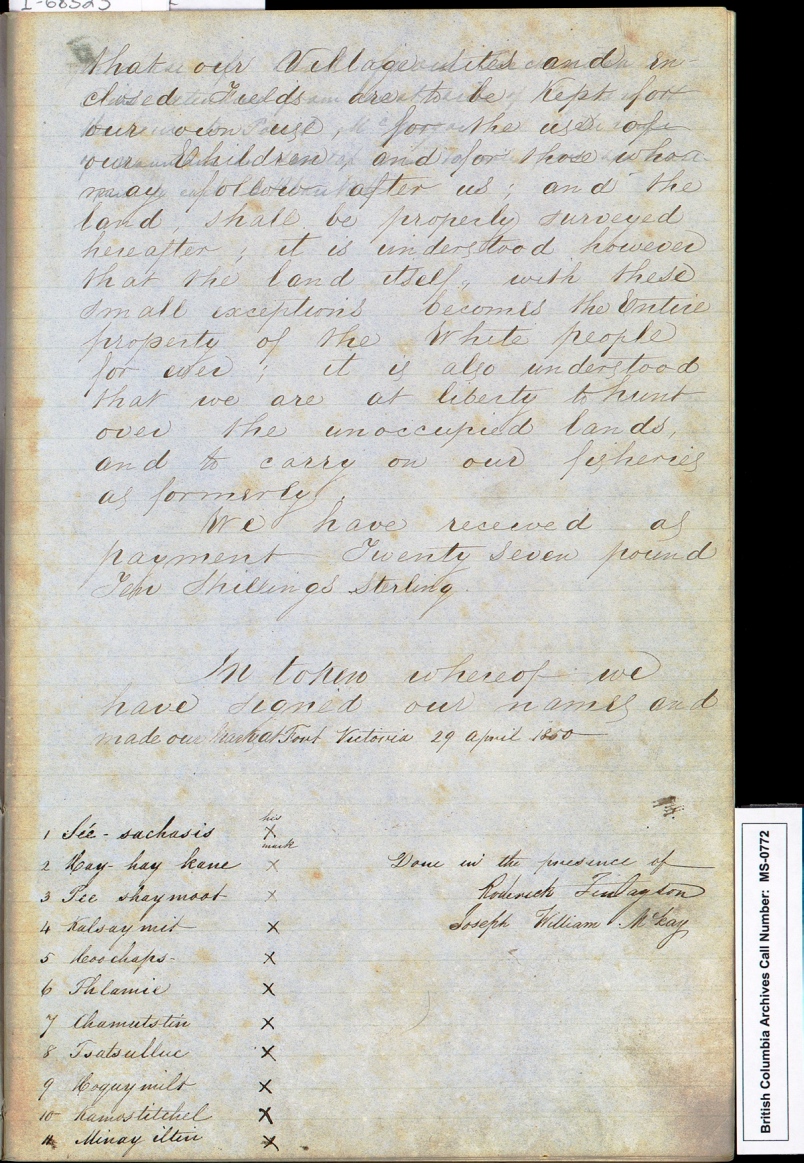

The pages of one of the Douglas treaties, this one covering lands from Esquimalt Harbour to Point Albert along Juan de Fuca Strait.

The written version of the Douglas Treaties recognizes specific W̱SÁNEĆ rights, they have been used by W̱SÁNEĆ people to win many legal battles, and they continue to be the subject of discussions with the Federal Government today.

However, the written version, each just over 200 words, does not provide the context or cultural nuances necessary for a full and accurate interpretation of what was agreed to. In a podcast called “Douglas’ Word,” Joni Olsen, a direct descendant of the W̱SÁNEĆ signatories, shares:

“I have always wondered, why would my people have given away their home, their survival, their power and their wealth? Or, in our terms, our relationship and our responsibility to the earth and our relatives. Why would we do that with no fight at all – just give it to the white man forever? There was always something missing for me.”

The written version of the Douglas Treaties was the result of two meetings in February 1852 between representatives of the Hudson’s Bay Company and W̱SÁNEĆ. At the end of these meetings, Douglas came away with two pieces of paper signed with X’s--the North and South Saanich Treaties–and the W̱SÁNEĆ people came away with around $200 worth of blankets. However, the parties still have differing perspectives on what actually happened that day.

From the perspective of Douglas, the ownership of the land was secured and war with W̱SÁNEĆ was prevented. But, from the perspective of the W̱SÁNEĆ people, something else entirely transpired.

For the W̱SÁNEĆ, the meeting was intended to address two grievances. The first was related to a timber dispute in Cordova Bay. Douglas and his men were harvesting timber and the W̱SÁNEĆ people sent four war canoes to the logging site, instructing settlers in no uncertain terms to “Tell your boss to take his men and his tools and go back to Victoria and cut no more trees.” (Elliott, The Saltwater People). The second grievance was the murder of a young messenger boy, related to the W̱SÁNEĆ Chief, while he was travelling between W̱SÁNEĆ villages.

With this in mind, the meetings would have been perceived much differently by W̱SÁNEĆ people than the written version indicates. The approximately $200 worth of blankets should be interpreted through the lens of W̱SÁNEC culture. In her podcast, Joni Olsen explains that blankets are a common form of payment given to those who witness important moments and those individuals are responsible for committing these moments to memory forever. Additionally, blankets are used to mark the significance of important events. Land was not something that was bought or sold by W̱SÁNEĆ people, let alone for $200 worth of blankets.

As legal scholar Hamar Foster noted–when discussing the Saanichton Bay Marina–stated:

“Douglas secured the approximately fifty square miles of the Saanich peninsula for a little over £100, which he paid to the Indians in Hudson’s Bay Company blankets at the 300% Company mark-up for non-employees. As the trial judge acknowledged [during Saanichton Marina Ltd. v. Claxton (1989)], the Indians ‘could not have thought of [such a transaction] as a purchase,’ and would not have regarded the woollen goods they received as payment for land. What seems much more likely is that they believed that they were agreeing to peaceful relations, to share the right to harvest certain resources, and to allow a limited number of colonists to occupy some of the lands they were not themselves occupying.”

The spirit of any agreement is contingent on both parties’ understanding and consenting to what is taking place. This would have been nearly impossible, as almost no W̱SÁNEĆ people spoke English at the time and no settlers spoke SENĆOŦEN. In addition to the language barrier, significant cultural differences existed. As discussed above, the concept of land ownership, a construct of colonialism, was not shared.

The signatures on the documents are also problematic. The names of the W̱SÁNEĆ people in attendance were transcribed properly into English, the “X’s” interpreted by settlers as signatures appear to be written by the same hand, and according to the oral tradition captured in The Saltwater People:

“Actually they didn’t call them X’s they called them crosses. They thought it was just a sign of sincerity and honesty. This was the sign of their God. It was the highest order of honesty.”

The written version of the Douglas Treaties don’t take into account any of these linguistic, cultural or contextual elements and differs vastly from the oral account. In fact, the written version is a virtual carbon copy of agreements used between the Crown’s colonial agents and Indigenous peoples as far away as New Zealand. While problematic, the Douglas Treaties are currently the only written agreements between Canada and the W̱SÁNEĆ people.

The W̱SÁNEĆ Leadership Council is actively seeking to correct the record by ensuring that the true meaning and intent of the Douglas Treaties is respected and implemented. By doing so, the W̱SÁNEĆ Leadership Council is hoping to return authority, jurisdiction, dignity, and benefits to the W̱SÁNEĆ people.

RECENT POSTS

How are we doing?

“Douglas secured the approximately fifty square miles of the Saanich peninsula for a little over £100, which he paid to the Indians in Hudson’s Bay Company blankets at the 300% Company mark-up for non-employees. As the trial judge acknowledged [during Saanichton Marina Ltd. v. Claxton (1989)], the Indians ‘could not have thought of [such a transaction] as a purchase,’ and would not have regarded the woollen goods they received as payment for land. What seems much more likely is that they believed that they were agreeing to peaceful relations, to share the right to harvest certain resources, and to allow a limited number of colonists to occupy some of the lands they were not themselves occupying.” Hamar Foster