The Creation of Indian Reserves and their Impact On The W̱SÁNEĆ Nation

The division and erosion of the W̱SÁNEĆ Nation into separate bands and onto tiny reserves was the result of many decades of concentrated efforts by colonizers to divide and weaken the Nation.

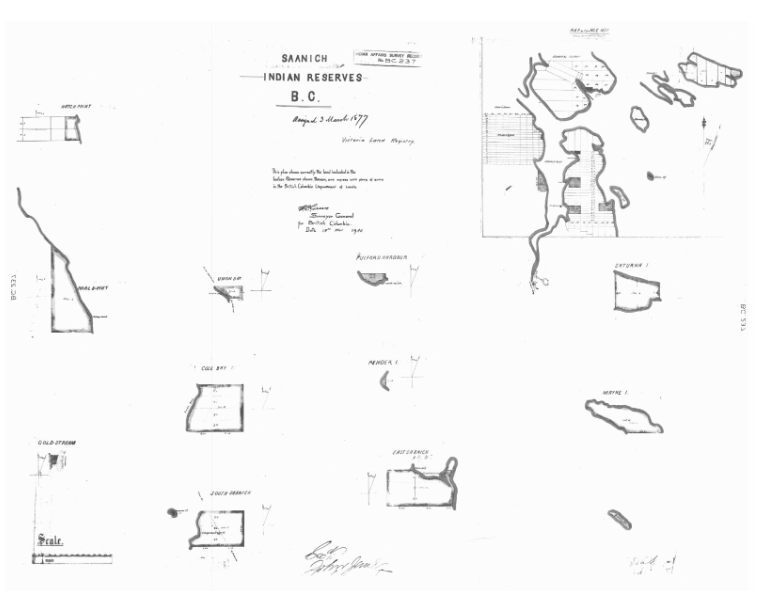

Shown above: The reserves created in 1877 for the “Saanich Indians.”

Before the reserve system

The names of the present-day W̱SÁNEĆ bands and reserves: Tsartlip, Tsawout, Tseycum, and Pauquachin originate from the English pronunciation of just a few of the many W̱SÁNEĆ villages dotted around what is now known as the Salish Sea. These villages were located throughout the traditional territory on the Saanich Peninsula, on the western shores of the Saanich Inlet, on the Southern Gulf Islands in Canada, and even on the San Juan Islands in what is now Washington State.

As Saltwater People, W̱SÁNEĆ economic activity was traditionally dictated by the weather and what was in season to hunt or fish. Accordingly, families would travel to and live in villages all around the traditional territory; harvesting, hunting, and fishing. W̱SÁNEĆ people traditionally had permanent winter villages and summer camps. Certain areas, like fishing spots, were passed on through the generations along with the responsibility of caretaking for these places. A fluid set of understandings existed between families for where they traditionally lived, hunted, and fished.

Eric Pelkey, a W̱SÁNEĆ Knowledge Holder, shares some of the oral history of his family prior to the reserve system;

“When my mother married my father in 1947 there was no such thing as separate bands, it was just the W̱SÁNEĆ people. My family lived mainly in Tsawout but they had longhouses on Pender island, Cordova Bay, Pender Canal, Active Pass, Winter Harbour on Saturna Island, and Ganges Harbour on Saltspring. My family had a lot of longhouses, they had more than the winter one here. They would move around depending on what they were harvesting.”

This lifestyle, in sync with moons and the tides, reinforced W̱SÁNEĆ people’s worldview—that the natural world was filled with plant, animal and natural relatives—with whom there is a sacred connection and responsibility to care for. “The word for mountain means gift. It comes from one of our fundamental stories when XÁLS threw stones and they grew into mountains. He took the people up to the mountain and told them, look after your relatives,” shares Kevin Paul, a W̱SÁNEĆ Knowledge Holder. “It’s an example of the differences in worldview between ourselves and colonizers. We did not relate to land from a perspective of ownership.”

These teachings were passed on through the generations, from knowledge holders to youth, both from within the greater community as well as the larger family unit.

Before the reserve systems, it was common practice for many generations and relatives to live in the same house. A leader did not inherit a house, but each family passing through that house owned the planks and materials that created the house. Along with the family’s longhouse materials, a family leader inherited the responsibility and rights of his or her family.

“Imagine all the things you would learn from all the people coming through the house. We view it as a sickness to be separated from each other,” explains Paul.

Another fundamental difference between traditional life and life in the reserve system was that previously women were very much present in community leadership and politics. Since colonization, the role of women has been severely reduced.

A timeline of reserve creation

1852 – On February 11th 1852 the Douglas Treaties were signed by representatives of the Hudson’s Bay Company and W̱SÁNEĆ. The treaties specified that in return for the sale of their lands on and near the Saanich Peninsula that their “village sites and enclosed fields” would be preserved for them and future generations. It also specifically guaranteed that the lands would be “surveyed hereafter” as a condition of the surrender. W̱SÁNEĆ oral history, of course, tells a different story.

1871 – British Columbia joins Canada in 1871, and reserve lands within British Columbia fall under the Indian Act. Under the Indian Act First Nations peoples and communities are prohibited from expressing their identities through governance and culture. The Indian Act replaced traditional structures of governance with band council elections. And, hereditary chiefs — leaders who acquire power through descent rather than election — are not recognized by the Indian Act.

1877 – On March 3rd 1877, the Saanich reserves–as guaranteed under the Douglas Treaties–were formally created for the “Saanich Indians.” A map outlining reserve lands is filed with the land registry in Victoria.

1931-1954 – Through a series of poorly attended meetings and votes, under the guise of negotiations, various colonial appointees began to assign the individual reserves to each of the W̱SÁNEĆ villages.

1940s-1960s – According to oral history, W̱SÁNEĆ people are relocated from their Gulf Island homes. As a result of the above meetings, the distinct W̱SÁNEĆ bands are formed and reserve land is formalized and assigned. Additional research is required to pinpoint the exact dates from the creation of the individual W̱SÁNEĆ bands.

How land was divided and reserves were set up

Working in tandem with the Residential school system, on a population reduced from tens of thousands to less than 500, the already reeling W̱SÁNEĆ people were then subjected to the paternalistic and arbitrary Indian Act.

In over 100 pages of correspondence between various colonial administrators between 1931 and 1954, the concerted effort to displace, dispossess, divide, label, and categorize the members of the W̱SÁNEĆ people is thoroughly documented.

This process was driven by an organized effort by settlers to group, categorize and assign W̱SÁNEĆ people to tiny tracts of land; based entirely on a belief system that could not be further from that of W̱SÁNEĆ people.

First, using the work of past anthropologists and earlier settlers, the colonial appointees began the process of documenting the names of the Villages along the peninsula and on and around the Gulf Islands. The result of this investigation is the anglicized place names now used to describe the various reserves. Next, settlers then set out to identify the heads of the families that lived in the villages. From there, colonizers set out to obtain “agreement” from these heads of families as to what land belonged to them.

Shares Paul, “The leaders were arbitrarily picked. My mother was disappointed in “her men,” Under the Indian Act, leaders were to be elected and they weren’t allowed to be women. The way things used to be, women were important advisors, both spiritually and politically, – although it doesn’t really fit to call it political.”

Remembers Pelkey: “One day the Church and the Government met with the heads of the families. They told them they were going around and meeting with different villages to set up reserves for the Indians. My great grandfather was just a fairly young man, 17 or 18 when he was recognized as the Chief. They were having hearings, and he, along with a group of headmen went to meet with them and said they wanted their villages protected. He was aware that under the treaty that the village sites were supposed to be saved. He asked them to save Ganges Harbour. He went before the Indian Reserve Commission when they were coming around. They promised him to listen but never honored their commitment.”

The extensive correspondence that took place between various colonial parties in regards to dividing the “Saanich” reserves may, at first glance, appear to describe a consensual process. Documented are meetings that occurred between heads of families and various Indian Act officials over the course of decades. The reality is that this process was anything but consensual. Shares Paul, “ We were becoming outnumbered.”

A particularly troubling example of one of these “votes” took place in 1954. The count was: “171 Indians absent, 70 present, 68 “for”, and 2 abstained from voting.” Explains Pelkey, “It wasn’t our process – so we didn’t go.”

In a letter dated July 15th, 1954 submitted within the report, LL Brown (Superintendent, Reserves and Trusts) acknowledges that the process may have been illegitimate: “The number of absentees is considerable and we will, therefore, have to ask the Departmental Legal Adviser as to whether or not the vote as taken can be considered a representative or whether, in such cases, we should follow closely the provisions of the surrender sections of the Indian act.”

Along with the forcible relocation of W̱SÁNEĆ people and the displacement from the traditional territory, W̱SÁNEĆ culture was also criminalized:

Shares Paul, “My Great Grandfather was all of a sudden told the way he was living was not allowed; that he could not hunt ducks using lamp lighting and he needed a paper to go fishing. He would get arrested over and over, and they would tow his canoe, tie his canoe to their boat expecting he would stay in it and be towed. Instead, he’d untie the rope and begin to paddle away. So they would attach his canoe again and this went on until they took his canoe.”

Soon after these “hearings,” Pelkey explains that the settlers started restricting where people could live and families were being removed from the Gulf and San Juan Islands. “A lot of the villages were destroyed when the reserve commissions went through. My grandfather Marshall told me, they tried to go and live out on some of the old village sites and were chased off because white people owned the land.”

The degradation of traditional transportation further separated and prevented contact with W̱SÁNEĆ relatives on the mainland, particularly those on the coast near “Point Roberts,” who, along with Saanich People, far outnumbered the colonizers at that time. Shares Kevin Paul, “The settler government discouraged our means of open seas travel to discourage us from travelling to visit our mainland relatives. As a replacement, they promised that a ‘better and safer’ method of transportation was coming and that W̱SÁNEĆ people would never have to pay for this new method of travel.“

The divisive impact of the reserve system

“The reserve system was purpose-built so people didn’t need to talk to each other anymore. Then block funding was set up so each band was competing against the other for resources. The reserve system first divided us and then pitted us against each other,” shares Paul, a W̱SÁNEĆ Knowledge Holder.

The creation of titles like “Reserve Indian” and “Off Reserve Indian” and “status” and “non-status Indian” further divided community members. When the Union of BC Indian Chiefs was established, it muted the voices of “off” or “non” reserve Indians as “they had no chief” according to the Indian Act and the reservation election system.

Additionally, hereditary leaders, specifically women, were no longer allowed to hold power and influence, as the Indian Act electoral system replaced a system of governance that had worked well since time immemorial. “The trust of having someone represent you well and with your desires and respect for you in mind was broken,” Paul continues.

Highways and paved roads in between the reserves further separated the Nation into smaller, disconnected areas. The reserves bear little if no resemblance to where traditionally, families would live. Shares Pelkey, “Tsawout is an amalgamation of all the families that used to live on the Gulf and San Juan Islands.” Agrees Paul, “Going from flexible boundaries between families to hard borders was not an easy thing for our people to adjust to.”

In the 1950s, the government formalized the creation of the Indian bands, the colonial government built offices in each reserve, and officially, according to the colonial government, it was no longer all W̱SÁNEĆ. Instead, the land was divided up according to the “agreements.”

Meanwhile, the majority of the traditional villages were destroyed or overtaken. The loss of villages at what is now known as Ganges Harbour or Poet’s Cove robbed W̱SÁNEĆ of access to traditional foods which has created negative health effects prevalent today.

Forced into individual housing disrupted the traditional way of living together, further dividing W̱SÁNEĆ people from their families and greater community and creating the foundation of the housing crisis and poverty experienced today.

The imposition of a colonialist culture had severe spiritual consequences as well.

“It took a while for us to learn the manner of standing against the man” commented Paul.

As it is said, “They tried to bury us but they did not know we were seeds”. In spite of the near destruction of the W̱SÁNEĆ Nation, the culture, practices, and reemergence cannot be denied.

Shares WLC Chairman Chief Don Tom, “As our elders have said, ‘when we disagree, the government wins.’ By standing together, the W̱SÁNEĆ will be a reckoning force within our Territory.”

To stay up to date on this article and others, please sign up for our newsletter.