On January 8th 1987 the Chiefs of Pauquachin, Tsartlip, Tseycum and Tsawout came together to sign the Saanich Indian Territorial Declaration. January 8th 2022 marks the 35th anniversary of this historic event.

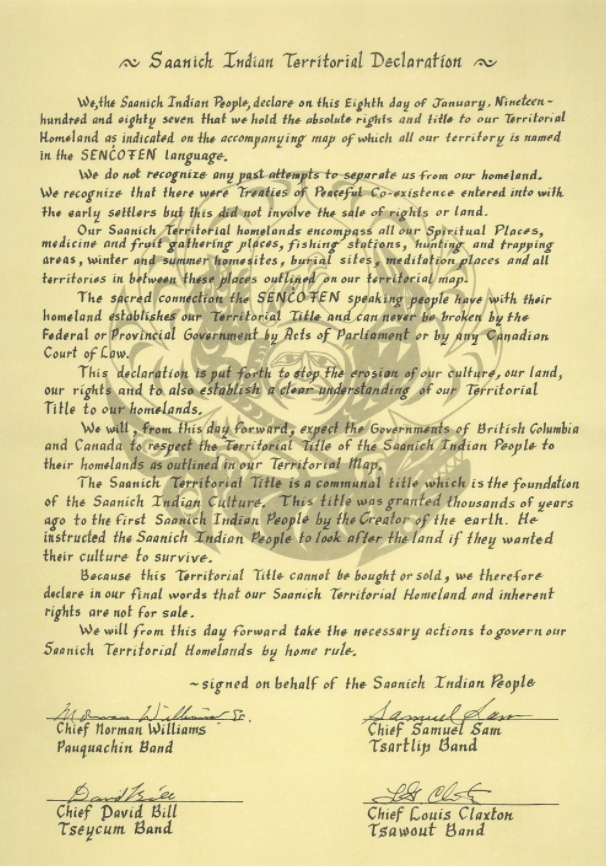

Shown above: the Saanich Indian Territorial Declaration. Click to enlarge

The declaration explicitly asserts W̱SÁNEĆ people’s absolute rights and title to the W̱SÁNEĆ Territorial Homeland. Despite the attempts of the Provincial and Federal governments to impose dominion over these lands for the past 170 years, our Chiefs declared that these rights are irrevocable. The declaration also makes clear the expectations for all levels of government and establishes a path forward for how they need to honour W̱SÁNEĆ rights and title.

The Saanich Indian Territorial Declaration was signed after over a hundred years of W̱SÁNEĆ people enduring a failed relationship with the Crown. This Crown, in this relationship, not only failed to fully recognize W̱SÁNEĆ rights and title, but consistently sought to undermine the Treaty relationship—at times denying its validity. Further, the Crown’s relationship with W̱SÁNEĆ people, which at the time of the signing of the Douglas

Treaties was based in mutual respect, became increasingly paternalistic without any consideration for W̱SÁNEĆ self-determination. This is exemplified best by the development of legislation that culminated in the Indian Act of 1876.

This Indian Act treated Indigenous people as children to be managed by the government while also suppressing and criminalizing Indigenous ways of life. Hunting, gathering, fishing, the management of forests through prescriptive burns, potlatches, winter ceremonials, and many other aspects of W̱SÁNEĆ life were impacted.

Through Section 141, the Act even went so far as to outlaw the hiring of lawyers and legal counsel by Indigenous people. This amendment effectively barred Indigenous peoples from advocating for their rights through the legal system. Eventually, the Indian Act expanded to such a point that virtually all Indigenous gathering was prohibited and could result in imprisonment. Despite this, organizations such as the Nisga’a Land Committee and the Native Brotherhood of British Columbia continued to organize the fight for Aboriginal rights and title underground throughout the early-20th Century.

While abhorrent in so many ways, the Indian Act legally distinguishes between Indigenous people and other Canadians and acknowledges that the federal government has a unique relationship with, and obligation to, Indigenous people. However, this obligation was recognized well before the Indian Act was created and forms the basis for the current Treaty relationship. The Royal Proclamation of 1763—a document intended to establish the basis for settlers governing the North American territories— explicitly states that Aboriginal title exists and that all land would be considered Aboriginal land until ceded by treaty. Despite this, in British Columbia, where the vast majority of the province has never been ceded by Indigenous peoples, the province continued to maintain that the Royal Proclamation does not apply to BC since it was settled after 763.

Due to BC’s refusal to recognize Aboriginal Rights and Title, W̱SÁNEĆ’s Philip Paul, along with many other BC Indigenous advocates like George and Bob Manuel, organized the now-famous Constitution Express of 1980, the cross-Canada train demonstration to Ottawa.

It took two years of raising concerns before an international audience—including the United Nations and the British Parliament—before the Canadian government finally agreed to include Aboriginal rights and title, in the newly-repatriated Constitution as Section 35.

Philip Paul and Bob Manuel in Ottawa during the Constitution Express demonstrations, 1980. COURTESY UNION OF B.C. INDIAN CHIEFS, F1030024

The inclusion of Aboriginal rights and title in the Constitution has subsequently been used in BC legal cases at every level—including at the Supreme Court of Canada—to weigh in on issues related to Aboriginal rights and title.

While many thought the Constitutional victory would provide protection for Aboriginal rights and title, in reality, the burden fell upon Indigenous Peoples to define—often through litigation—the nature and quality of those rights. Further, while Section 35 does provide some protection, Stó:lo author Lee Maracle argues it also reinforces colonialism by recognizing Canadian law as supreme, abandoning the concept of true nation-to-nation relationships.

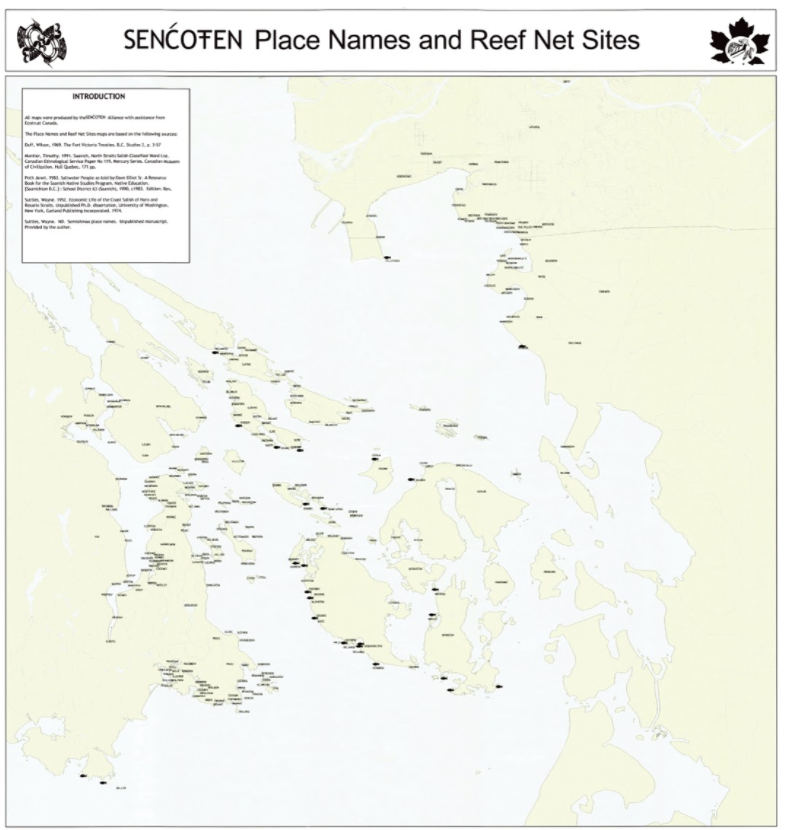

This is the context that our Chiefs found themselves in 1987 when they issued the Saanich Indian Territorial Declaration and asserted irrevocable rights and title to our Territorial Homeland: throughout the Gulf Islands, San Juan Islands, and on the east and north coasts of the Saanich Peninsula, as well as northeast across Georgia Strait to Boundary Bay. Our territory included the Saanich Inlet and deep into the forest lands on its west side. On the Saanich Peninsula itself, our land went south as far as PKOLS (Mount Douglas), and from there across to W̱QENNELEȽ (Mt. Finlayson) and SELE₭TEȽ (Goldstream).

The declaration made by our Chiefs in 1987 marked the beginning of a shift in interactions with all levels of government. The W̱SÁNEĆ Leadership Council continues to uphold the calls to action made 35 years ago working to push the federal, provincial, and municipal governments away from the denial of Aboriginal rights and title, instead working to return and rename the W̱SÁNEĆ territorial homeland in recognition of our territorial title and inherent rights.

Have a look below at the text of the Saanich Indian Territorial Declaration and newspaper clippings from 1987 covering this important moment in W̱SÁNEĆ history

The Declaration reads:

We, the Saanich Indian People, declare on this eighth day of January, 1987 that we hold the absolute rights and title to our Territorial Homeland as indicated on the accompanying map* of which all territory is named in the SENĆOŦEN language.

We do not recognize any past attempts to separate us from our homeland. We recognize that there were Treaties of Peaceful Co-existence entered into with the early settlers but this did not involve the sale of rights or land.

Our Saanich Territorial homelands encompass all our spiritual places, medicine and fruit gathering places, fishing stations, hunting and trapping areas, winter and summer homesites, burial sites, meditation places and all territories in between these places outlined on our territorial map.

The sacred connection the SENĆOŦEN speaking people have with their homeland establishes our Territorial Title and can never be broken by the Federal or Provincial Government by Acts of Parliament or by any Canadian Court of Law.

This declaration is put forth to stop the erosion of our culture, our land, our rights and to also establish a clear understanding of our territorial title to our homelands.

We will, from this day forward, expect the Governments of British Columbia and Canada to respect the Territorial Title of the Saanich Indian people to their homelands as outlined in our Territorial Map.

The Saanich Territorial Title is a communal title which is the foundation of the Saanich Indian Culture. This title was granted thousands of years ago to the first Saanich Indian People by the Creator of the earth. He instructed the Saanich Indian People to look after the land if they wanted their culture to survive.

Because this Territorial Title cannot be bought or sold, we therefore declare in our final words that our Saanich Territorial Homeland and inherent rights are not for sale.

We will from this day forward take the necessary actions to govern our Saanich Territorial Homelands by home rule.

-Signed on behalf of the Saanich Indian People

Chief Norman Williams

Pauquachin Band

Chief Samuel Sam

Tsartlip Band

Chief David Bill

Tseycum Band

Chief Louis Claxton

Tsawout Band

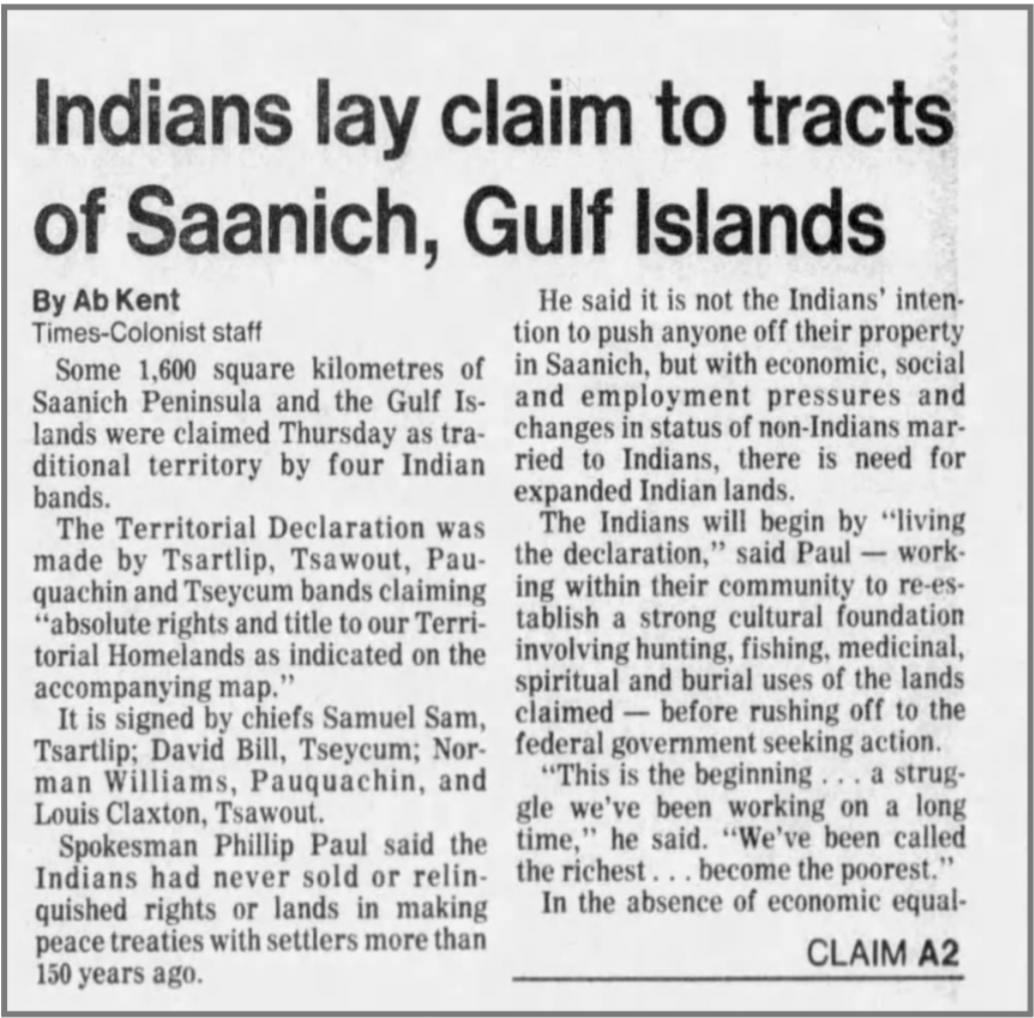

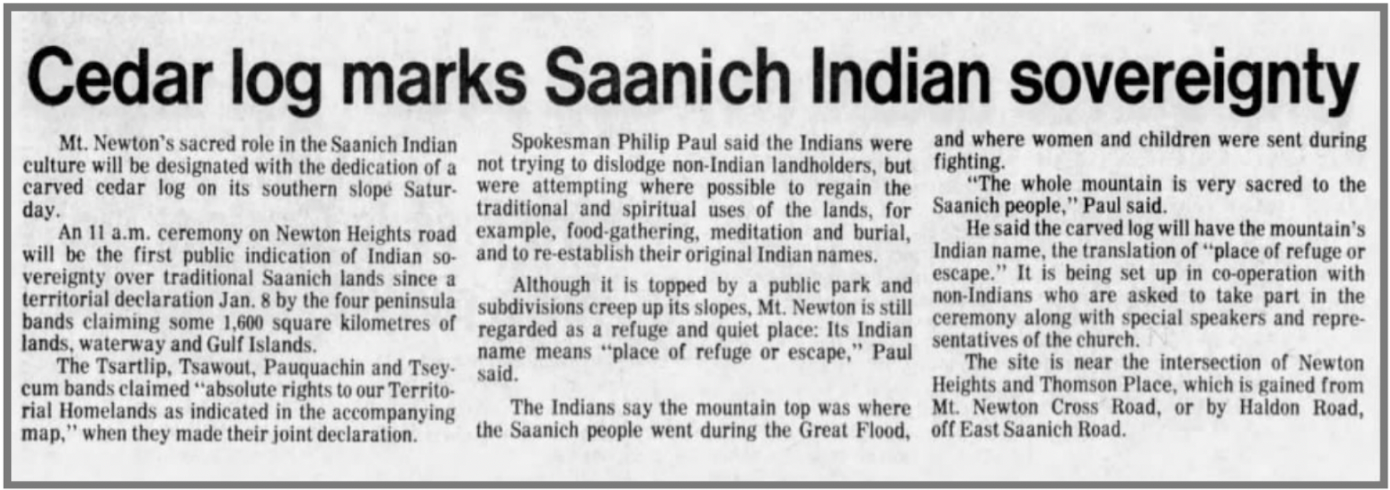

Shown Above: Clippings from the Times Colonist, Friday, January 9th, 1987

Shown above, SENĆOŦEN place names. Click here to expand

Shown above a clipping from the Times Colonist February 5th, 1987,