WLC continues to advocate for Hunting rights through community consultation & position paper

The W̱SÁNEĆ Leadership Council (WLC) has finished many months of work gathering the stories, perspectives, and experiences of W̱SÁNEĆ people who exercise their right to hunt. All of this data has, for the first time, been collected and outlined in a position paper.

This document, the W̱SÁNEĆ Position Paper on W̱SÁNEĆ Hunting Rights, was developed in conversation with community and includes stories from the W̱SÁNEĆ Hunters Committee and Hunters Conference, interviews stored in databases, and historical research into infringements on Douglas Treaty rights.

This Hunting Position Paper is the first and most comprehensive source of facts detailing the erosion of the W̱SÁNEĆ Douglas Treaty right to hunt in the years since colonization. In addition to detailing W̱SÁNEĆ history, this paper also includes a thorough review of case law as it pertains to the Douglas Treaties and the right to “hunt and fish as formerly.”

In the position paper, the WLC insists the Province acknowledge the Douglas Treaty rights of W̱SÁNEĆ hunters “to hunt over the unoccupied lands . . . as formerly” as well as take other actions towards reconciliation.

The position paper focuses on eight key things to change, including:

- The implementation of Douglas Treaty rights

- Moving away from provincial concepts of W̱SÁNEĆ territory (W̱SÁNEĆ territory is much larger than the government understands)

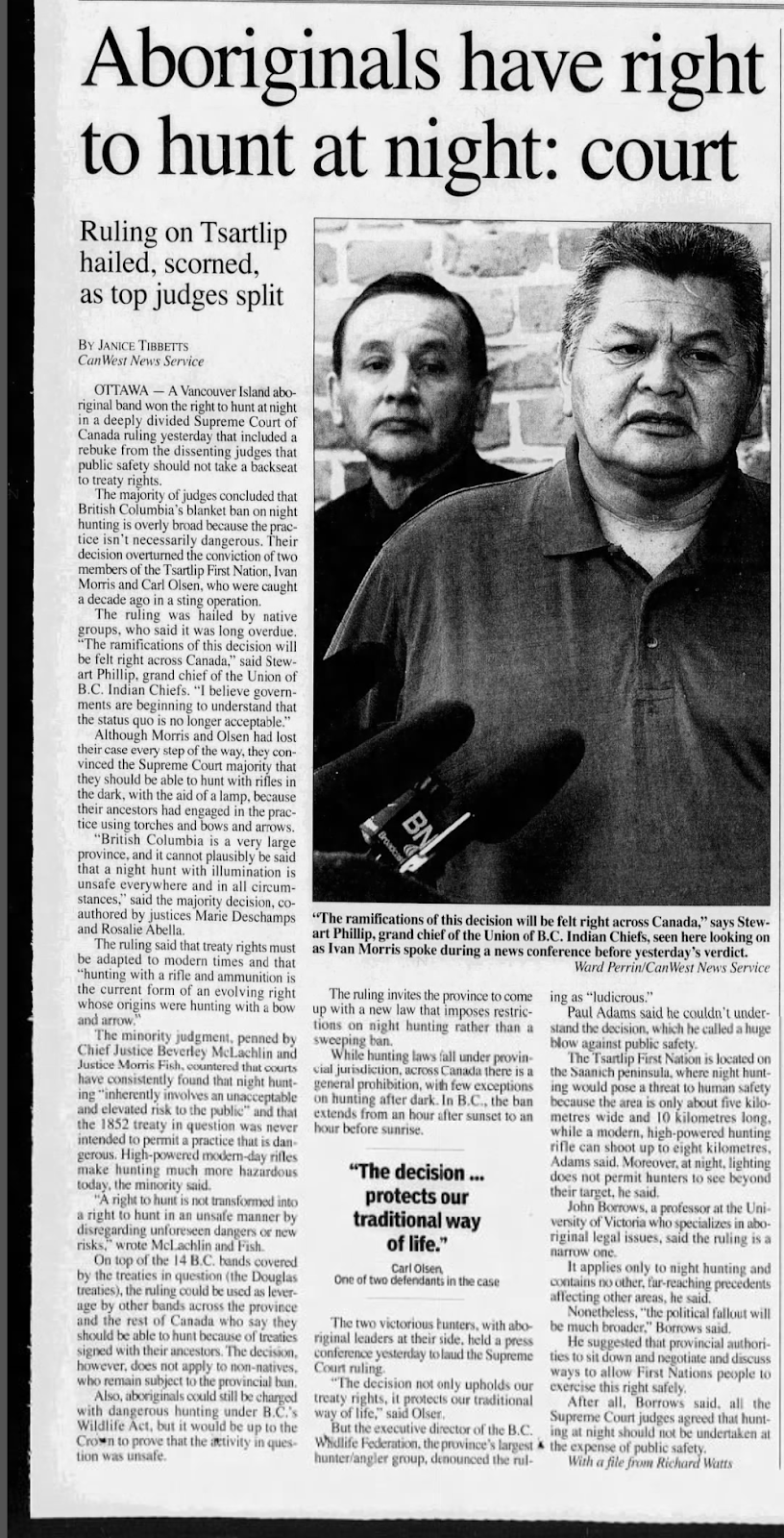

- The implementation of the many court victories won by W̱SÁNEĆ people

- The way wildlife is allocated and how W̱SÁNEĆ people are not prioritized

- The lack of recognition of the W̱SÁNEĆ economic right to hunt

- The loss of W̱SÁNEĆ land and territory

- Harassment of W̱SÁNEĆ hunters by conservation officers, municipal police and RCMP

- Incorrect publicly available information about W̱SÁNEĆ rights

Though this is not an exhaustive list of issues W̱SÁNEĆ hunters face, it serves as an important starting point for documenting the systemic changes that need to take place. Current constraints within the provincial system make it difficult for the government to address all of these issues right away, but a work plan will be created to prioritize certain issues that can be remedied more quickly.

Implementation of Douglas Treaty rights

The implementation of Douglas Treaty rights is the position paper’s central claim. W̱SÁNEĆ people have hunted on the W̱SÁNEĆ land since time immemorial, which isn’t just limited to hunting. It includes caring for the land, engaging in cultural practices, and passing on sacred hunting traditions. Additionally, hunting is an important part of W̱SÁNEĆ governance systems, economic relationships, social status, and wealth creation.

The Douglas Treaty acts as a promise to honor these inherent rights, given to W̱SÁNEĆ people by XÁLS / the Creator, and it allows for the right to hunt without the government or other regulatory bodies’ intervention. However, the government’s indirect and direct actions have continuously interfered in this right to the point where it is not viable for many W̱SÁNEĆ people. The W̱SÁNEĆ Leadership Council is aiming to create an environment where W̱SÁNEĆ hunters are free to feed and provide for their families, and to connect with this cultural practices deeply tied to W̱SÁNEĆ identity.

Provincial concepts of W̱SÁNEĆ territory

Another key area of the position paper is to dispute the provincial government’s definition of W̱SÁNEĆ territory. The provincial government has created arbitrary maps of W̱SÁNEĆ territorial territory, often confining it to the Saanich Peninsula, a small portion of Malahat, and the Southern Gulf Islands. In reality, many W̱SÁNEĆ hunting areas fall outside these lines and W̱SÁNEĆ people, through family ties, are able to hunt under W̱SÁNEĆ laws on the mainland and up Vancouver Island. However, Conservation Officers, municipal police, and the RCMP enforce the Province’s ideas of W̱SÁNEĆ territory, putting W̱SÁNEĆ hunters at continued risk of harassment by law enforcement.

Implementation of court decisions

W̱SÁNEĆ people have won in court time and time again, and, for the most part, these victories have not yet been implemented. W̱SÁNEĆ hunting rights are not recognized by the province. As a result, Case law is an important part of the position paper, and, in the position paper, the WLC describes the ways the government is acting in direct conflict with numerous legal decisions.

For example, R. v. Bartleman states that the Douglas treaty hunting right includes the right to hunt in unoccupied land in all traditional hunting locations, not only within the area described in the treaty. In 1852 the economy of the W̱SÁNEĆ people was based on hunting and fishing at traditional locations throughout a large geographic area, providing access to resources when and where they were in the best supply. This is currently not considered by Provincial hunting territorial guidelines, putting our hunters at risk of being charged when hunting ‘out of territory’.

Allocation Priorities

The position paper also describes the Province’s misaligned allocations that fail to prioritize W̱SÁNEĆ hunters who are hunting the Douglas Treaty.

For example, the province determines how wildlife is allocated. Wildlife allocation determines how many animals are allotted to each group, who are often prioritized in this order: Wildlife conservation and sustainability, First Nations’ needs for food, social and ceremonial purposes, Resident hunting opportunity, and Non-resident hunting opportunity. W̱SÁNEĆ people, as they often hunt outside what the province considers W̱SÁNEĆ territory, are not included in this list, not even under the “First Nation’s needs for food, social and ceremonial purposes. This conflicts with what’s been promised to W̱SÁNEĆ hunters under their treaty rights.

In the position paper, W̱SÁNEĆ hunters describe how these allocation priorities criminalize W̱SÁNEĆ hunters, creating conflict between enforcement officers and W̱SÁNEĆ people. Further, these polices create tension between W̱SÁNEĆ people whereby W̱SÁNEĆ hunters are expected to ask permission of local First Nations (despite having familial rights to hunt in these places) who are protective of their allocation number. W̱SÁNEĆ hunters have noted that there is a double standard here: settler hunters are not expected to seek permission from local First Nations.

Lack of recognition of W̱SÁNEĆ economic right

The paper also asserts that W̱SÁNEĆ hunters have an economic right to hunt. The practice of selling/trading hunting bounty has always been practiced and provides modern-day opportunities to create livelihoods within the community. However, under the Wildlife Act, it is illegal to exercise this right. Conservation officers who enforce these regulations often harass and arrest W̱SÁNEĆ people for harvesting. This has created immeasurable damage, limiting W̱SÁNEĆ economic growth and traditional practices.

Loss of land and territory

Another major challenge the WLC has identified is the loss of land and territory. When discussing private forestry lands, the W̱SÁNEĆ hunters mentioned the problem of locked forestry gates and the continued deforestation which both impede the W̱SÁNEĆ hunters’ right to “hunt as formerly”. The provincial permits which have approved these projects are also responsible for destroying wildlife habitats. Ignoring the rights of animals to have healthy habitats creates an imbalance in the land and increased hunting difficulties.

The loss of large natural areas on the Saanich Peninsula, like Bear Mountain, means W̱SÁNEĆ hunters run the risk of hunting outside the area the province defines as W̱SÁNEĆ territory. Privatization, logging, and the expansion of residential properties continues to shrink the area W̱SÁNEĆ hunters can safely access.

In 2021, the BC Supreme Court ruled in favour of the claim by Blueberry River First Nation that the provincial government failed to uphold Treaty 8, protecting their right to hunt, trap and fish on their traditional territory. The Court declared that due to the high number of developments in Blueberry River First Nation’s territory, the Province has allowed the degradation of the environment to such an extent where the Blueberry River First Nation’s treaty rights have suffered a “death by a thousand cuts.” This verdict vividly describes the cumulative impact of ongoing infractions on treaty rights that W̱SÁNEĆ hunters also experience.

Harassment by conservation officers, municipal police and RCMP

The “fear of arrest” perpetuated by the conservation officers is an ongoing barrier to W̱SÁNEĆ people actively hunting. The position paper outlines years of documented interactions between W̱SÁNEĆ people and conservation officers, municipal police and the RCMP. These exchanges are often intimidating and violent, resulting in arrests and confiscation of firearms and meat.

The intimidation and threat used by authorities towards W̱SÁNEĆ hunters while out hunting and in their own homes not only impacts existing W̱SÁNEĆ hunters but discourages younger community members from participating in their cultural practices. In the position paper, W̱SÁNEĆ hunters emphasized the need for law enforcement to undergo cultural training to improve this strained relationship. Further, the WLC has advocated for alternate dispute resolution processes instead of arrests and fines.

Incorrect information publicly available

Finally, the need to address incorrect publicly-available information about W̱SÁNEĆ hunting is championed by the W̱SÁNEĆ Leadership Council. In addition to the numerous barriers already described, W̱SÁNEĆ hunters experience racism and harassment from the public and law enforcement, stemming from misinformation about traditional hunting practices. By engaging in public awareness campaigns aimed to correct misinformation and prevent racism, the public will gain a deeper understanding and appreciation for W̱SÁNEĆ hunters.

Now that these concerns have been thoroughly documented, and are gathered for the first time in one place, the W̱SÁNEĆ Hunting Position Paper can be used as an asset to insist on tangible steps towards reconciliation. With ongoing community consultation, the conversation with the Provincial government is intended to tackle these issues directly.

In preliminary conversations, the Province has responded positively with intention to take appropriate steps to reconciliation.

Though the road ahead is long, the WLC is committed to advocating for W̱SÁNEĆ Douglas Treaty and Hunting rights on behalf of community.

Stay up to date on this story and others, sign up for our newsletter.